The 1933 MLB All-Star Game: How Baseball Revived American Spirits During the Great Depression

Born from economic desperation and media innovation, the first All-Star Game wasn’t just a sporting event, it was a strategic play to save baseball and lift a nation.

If you liked this article, you can support me with a tip at Buy Me a Coffee. Tips go toward things like research snacks, quiet writing time, and keeping the kids from opening my laptop mid-draft!

This Tuesday, Major League Baseball will host the 93rd All-Star Game in Atlanta, Georgia. The spectacle we know today has deep roots, but it wasn’t born out of whimsy or tradition. It was created in 1933 as a strategic response to the economic despair of the Great Depression, a game born of necessity, not luxury, designed to bring fans back to the ballpark and restore baseball’s cultural relevance.

The 1933 Major League Baseball All-Star Game, often mythologized as a spontaneous celebration of national unity, was in fact a meticulously curated media invention designed to salvage both the sport’s cultural capital and a nation’s fraying optimism. Amid the depths of the Great Depression, when Americans lost not just jobs and homes but belief in their institutions, baseball positioned itself as a redemptive force. Indeed, many American men spent their spring in Florida trying to earn a spot on a Major League roster—not out of dreams of stardom, but out of desperation for a steady paycheck.

Yet the first Midsummer Classic did not emerge from the grassroots. It was orchestrated; top-down, editorially driven, and anchored in spectacle.

The architect of this so-called “Game of the Century” was Arch Ward, the 36-year-old sports editor of the Chicago Tribune. Ward, more promoter than journalist, seized on the opportunity to tie baseball to the city’s Century of Progress World’s Fair. He framed the event as civic contribution, baseball’s gift to the people during hard times. In reality, it was calculated brand management. By organizing a one-off contest featuring the best of the American League against the best of the National League, Ward effectively created baseball’s first cross-league exhibition at a moment when the sport’s gate receipts were tanking and its cultural relevance was in decline.

Ward understood the moment’s stakes. He sold the All-Star Game as both a populist gesture and a patriotic obligation. Fans would vote for the starters, lending the illusion of democracy. The game’s proceeds would go to a fund for retired, destitute players, adding moral gravitas to what was fundamentally a promotional stunt. Even the choice of Comiskey Park over Wrigley Field, determined by coin toss, was spun as symbolic. The White Sox’s stadium could hold more fans, and its proximity to the World’s Fair grounds made it more ideologically aligned with Chicago’s centennial messaging: progress, unity, resilience.

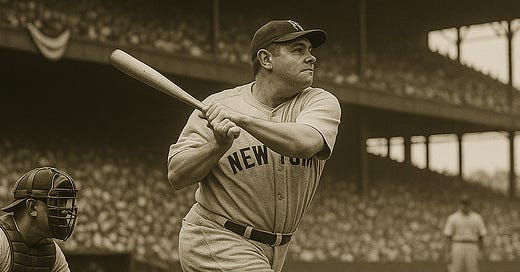

On the field, the players played as if it mattered. Ruth homered. Frisch answered. The stars, Gehrig, Foxx, Hubbell, Klein, gave the game teeth. But even in its execution, the event was more about narrative than competition. The American League’s 4–2 victory felt incidental compared to the cultural script playing out. Babe Ruth, the aging icon, hit the game’s first home run and made a leaping catch in the outfield, essentially canonizing himself in real time. It wasn’t just a baseball moment—it was propaganda. The subtext was unmistakable: America may be down, but it still has its heroes.

The game worked. Fans packed Comiskey. Papers across the country hailed the event as a “new tradition.” Commissioner Landis, initially skeptical, declared it a resounding success. Within a year, what had been a Depression-era experiment became institutionalized. And that is the true legacy of the 1933 All-Star Game. It marked the moment when baseball fully embraced performance, not just athletic, but cultural. It was not the sport’s most competitive game. It was, however, its most important illusion.

The 1933 All-Star Game didn’t rescue America, but it reminded Americans what redemption looked like. And that was enough.

If you liked this article, you can support me with a tip at Buy Me a Coffee. Tips go toward things like research snacks, quiet writing time, and keeping the kids from opening my laptop mid-draft!